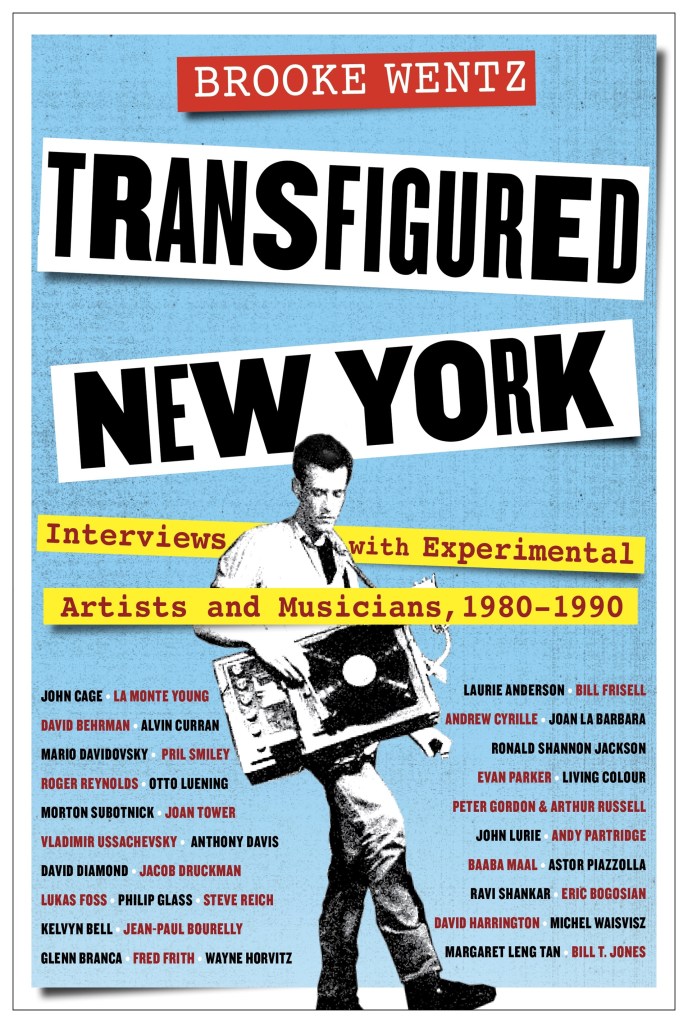

I can think of no better way of describing the eclectic, diverse, inscrutable musical melting pot that was New York in the late 1970s and early 1980s than a moment recounted by Brooke Wentz in her book Transfigured New York, a collection of radio interviews made between 1980 and 1990.

Wentz, who presented a long-running, adventurous radio show called Transfigured Night on New York’s WKCR-FM, was interviewing dexterous avant garde jazz bassist Andrew Cyrille in September 1986. Cyrille was midway talking about spontaneity and improvisation. However, the interview needed to be cut short because Wentz’s next guest had arrived. That next guest was the composer John Cage. On one level you could see this event as two different generations passing each other, metaphorically perhaps, in the corridors of culture; I like to think that it actually demonstrates how many musical forms could co-exist and thrive simultaneously in New York. The Brazilian percussionist Cyro Baptista nails it when he describes the city as “a caldron of misfits from all over the planet.”

Manhattan, geographically, is an island of just 23 square miles. Small and compact when contrasted with sprawling cities like London or Los Angeles, it’s hard to think of anywhere else that’s contributed so much to music, and, within that so much so-called ‘experimental’ music. Wentz’s radio show acted as a critical portal into that unfolding cultural significance, while her interviews with key figures – selected and collated in Transfigured New York – were illuminating insights into the motivations and works of figures that operated on music’s wild and essential fringes.

Wentz began her radio show in 1980. Starting then was important, as it allowed her to catch some of the architects of contemporary music before they passed away, or before resonant personalities like La Monte Young became reticent about being routinely interviewed. Her interviews with some of electronic music’s founding fathers – the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center team of Vladimir Ussachevsky and Otto Luening in particular – are illuminating and full of details that were new to me. They each shine a light on their atypical paths to electronic music, and how the earliest electronic studios were themselves started. One especially interesting area was around how progressive pioneers like Ussachevsky were with early computers, long before their use as creative – rather than functional – tools had been identified.

Transfigured New York is divided into nine sections – ‘The Founding Theorists’, ‘The Materials Scientists’, ‘The Composers’, ‘The Iconoclasts’, ‘The Vocalists’, ‘The Dissenters’, ‘The Popular Avant-Garde’, ‘The Global Nomads’, ‘The Performance Artists’. These are convenient, but relatively arbitrary groupings given how fluid New York’s cultural diaspora was, and how welcoming a city it was for visiting performers such as Ravi Shankar. Each interview is also accompanied by smaller, Post-It Note-style excerpts. These footnotes – with everyone from Meredith Monk to Ikue Mori to Zeena Parkins – aren’t in any way indications of lesser importance, but they go a long way to reflecting how many individuals were hard at work setting up New York as the crucible of post-War creativity.

As Wentz’s show – and her musical research – evolved, she began embracing African music. The latter interviews of the book bring this personal interest to life. She excitedly recounts a trip to Africa and hanging out at Baba Maal’s Senegalese home while there. Happily, for Wentz, New York’s ever-evolving music frontier was also embracing broader cultural inputs more or less simultaneously, and her radio interview with Maal is undoubtedly among Wentz’s most impassioned conversations.

Comprehensive though Transfigured New York is, I was left feeling that there were other sides to this story that need to be told. Interviews with Sonic Youth’s Lee Ranaldo, Rhys Chatham and Glenn Branca each highlight how easily the so-called avant garde meshed with No Wave. Wentz hints at that when interviewing Peter Gordon about his Love Of Life Orchestra : “You’ve said that the group is an attempt to create a ‘democratic music’ that includes people from all sorts of backgrounds – classical music, rock, funk, poetry, rock, funk, poetry, visual art. That seems like a pretty good reflection of the city’s downtown scene.”

We get a tantalising glimpse, again, of how possible it was for different scenes to cohabit when artist Mikel Rouse talks about Philip Glass performing at Peppermint Lounge, and Glass himself talking about how his arpeggio-filled minimalist classical music was embraced by rock music fans. The apparent inconsistency between reading a wonderfully in-depth interview with John Cage where he talks about not enjoying noise, and another with Glenn Branca where he talks about Cage appreciating the volume he operated at quite honestly blowed my mind, but my mind was blown on almost every page of this engaging, near-exhaustive collection.

Ultimately, what Wentz’s book reaffirms is that New York, during the period she covers, was a small island with some of the biggest ideas and contributions. These first-hand accounts are among the most illuminating pieces I’ve ever read with players that often feel inaccessible. To have so many of them all surveyed in one book, just like the sheer number of important experimental musical figures who have been active in Manhattan, is a gift to us all.

Words: Mat Smith

Transfigured New York by Brooke Wentz was published November 16 2023. With sincere thanks to Meredith Howard at Columbia University Press, Gretchen Koss at Tandem Literary and Reed Hays.

(c) 2023 Further.