What happens if the left hand doesn’t know what the right hand is doing? What if there are two left hands and two right hands? What if both left hands don’t know what both right hands are doing?

I could go on subdividing this conundrum up a few more times, but I won’t. I won’t, because it’s irrelevant. Irrelevant because, having watched performances of Brahms’ Variations On A Theme By Robert Schumann, Schubert’s Variations On An Original Theme In A-flat Major and Leontovych’s Shchedryk by Ukrainian pianist brothers Alexei and Sasha Grynyuk – two pianists playing the same piano, together – what I witnessed was an example of complete harmonious synchronisation. Then again, the Grynyuk brothers are two esteemed, award-winning musicians, so nothing short of perfection should have been expected.

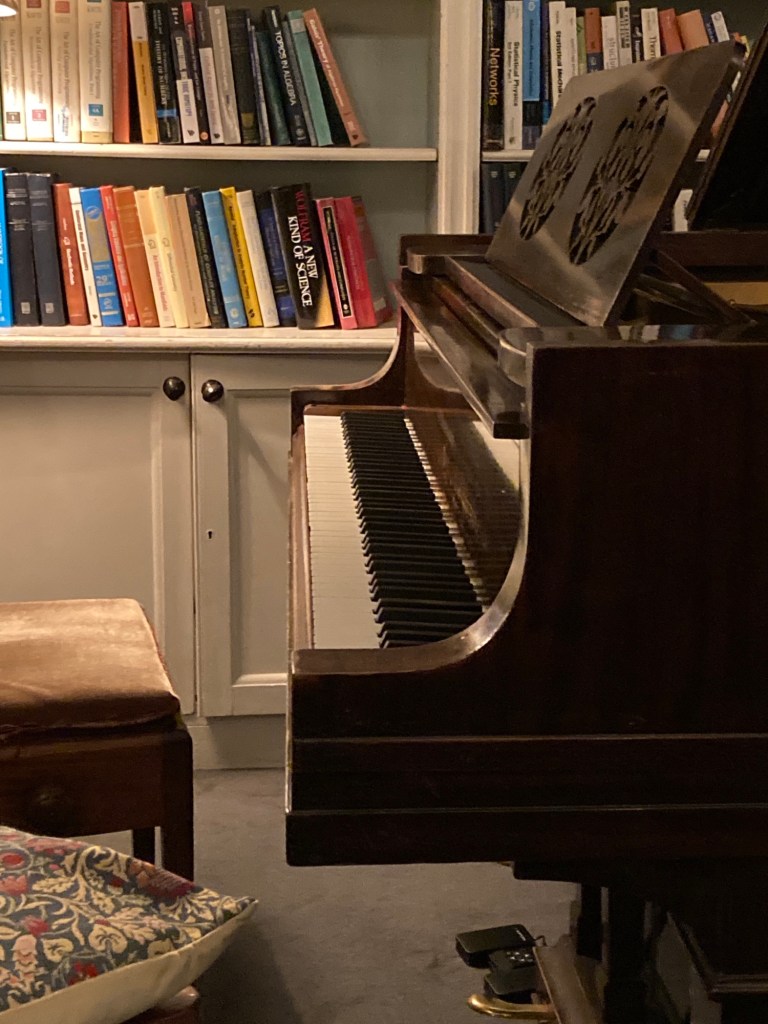

Watching their four hands frantically moving across the keys of the antique Steinway piano was a mesmerising display of dizzying dexterity. I watched Vanessa Wagner performing Philip Glass pieces at the Royal Albert Hall a few years ago and I was reminded of her lightning fast performance while watching the Grynyuk brothers as their hands raced at impossibly high speeds across the keys. It was like a display of kinetic energy; appropriate, given that the London Institute for Mathematical Sciences is located at the Royal Institute, where Michael Faraday conducted his pioneering experiments in energy.

It was also, occasionally, a little stressful to watch from a front-row seat that afforded a perfect view of those hands clustered at the centre of the keyboard. I watched, simultaneously in awe of what I could see, and strangely fearful that their hands might collide. It felt like there wasn’t enough space for their hands to co-exist at the instrument together. I anticipated moments of unintentional disharmony through some sort of mid-melodic crash, but, of course, there were none. See my previous comment about their award-winning status.

The two pieces were punctuated by a lecture by Professor Yang-Hui He, a Fellow at the London Institute for Mathematical Sciences (and self-proclaimed failed musician), who posited that the true architect of harmony was Pythagoras. Exploring the mathematical theory that explains the note intervals of scales and different harmonic patterns used in Chinese / Japanese, Western and Indian scales, I’ll be completely honest that I wished I’d paid more attention in both my music and maths lessons. It was just as baffling, to a maths novice like me, as trying to untangle the four Grynyuk hands as they played, but it involved fractions, and nothing is more likely to induce educational PTSD in me than trying to fathom fractions all over again.

Self-evidently, this piece is a departure from the usual words placed here on Further. It illustrates that I know very little about musical (or indeed mathematical) theory. Bearing in mind that my two careers – in finance and music writing – rely on a degree of knowledge of both of these, that’s a fairly brave admission.

It also illustrates that I’m more than happy to be put in situations where I am materially outside of the comfort zone in which I tend to operate. It also refutes, to my mind, the notion that your appetite for musical exploration atrophies as you get older. I’ll continue to seek out enlightening, enlivening and mind-expanding musical experiences like these until my ears fully fail me.

With sincere thanks to Katya Gorbatiouk and Sarah Myers Cornaby for the invite.

Words: Mat Smith

(c) 2026 Further.

You must be logged in to post a comment.